In January 1919, a huge harbourside molasses tank in Boston, Massachusetts containing over two million gallons of the thick, black treacle made from refined sugarcane ruptured. The accident spilled over 12,000 tonnes of liquid into the nearby streets in a tidal wave that killed 21 people and injured a further 500.

The tank belonged to the Purity Distilling Company, a subsiduary of the United States Industrial Alcohol Company, which used ethanol refined from molasses to make a number of industrial alcohols, munitions and alcoholic drinks. A large harborside tank, located on Commercial Street on the city’s quayside, allowed molasses to be offloaded directly from cargo ships and stored, before being transferred by pipeline to a processing plant. Measuring 15 metres in height and around 27 metres in diameter, the tank was thought to be close to capacity at the time of the accident: 2.3 million US gallons (8.7 million litres).

Unseasonal sunshine on the morning of January 15 1919 saw temperatures rise from the freezing conditions of the previous few days. At the same time, a ship offloaded a cargo of molasses into the tank, warming it to reduce viscosity and make the transfer easier. The combination of warm molasses being added to the cold stock in the tank and rising temperatures resulted in thermal expansion. The tank burst and subsequently collapsed at around 12:30pm. Witnessed described a low rumble similar to a train passing, as well as the ground shaking and a sound like machine gun fire caused by rivets being shot out of the tank.

A wave of molasses up to eight metres in height rapidly flowed out into the nearby street, reaching speeds of 35 miles per hour. The high density of molasses gave the wave a great deal more kinetic force than water, resulting in nearby buildings being crushed and the Boston Elevated Railway being badly damaged. One truck was picked up by the wave and swept into Boston Harbor.

While some of the casualties were killed by the force of the initial wave or after being struck with debris, others drowned in the thick, almost inescapable molasses, which quickly become increasingly viscous in the cold temperatures. In total, 21 people were killed, as well as a number of horses and dogs, similarly trapped in the thick black liquid.

Docked nearby was the USS Nantucket, a training ship of the Massachusetts Nautical School. Lieutenant Commander HJ Copeland led a rescue party of 116 cadets to the scene, with some forming a cordon to keep back curious bystanders while others waded into the flood to drag out survivors. The effort was soon joined by police, Army, Navy and Red Cross personnel, many of whom entered the molasses to provide first aid to those trapped.

Despite the number of rescuers progress was slow, hampered by the challenge of moving in the thigh-deep molasses and the difficulty of recovering or even finding victims. Rescue efforts continued for four days, after which many of the dead remained unidentified. Some victims had been swept into the harbor and were not found until months later.

A class-action lawsuit was brought against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company. While the company argued that the tank had been blown up by anarchists in protest against the munitions some ethanol was used to produce, it was eventually found liable. In total USIAC paid out $628,000 in compensation, around $9 million in modern terms. The company were found to have been negligent in failing to address leaks in the tank, instead painting it brown to hide the leaking molasses, as well as ignoring groaning sounds when it had previously been filled.

Cleanup efforts took hundreds of workers months to complete, with the water of Boston Harbor stained dark brown until the following summer. For decades after the area was permeated by the sweet smell of molasses, particularly on hot days.

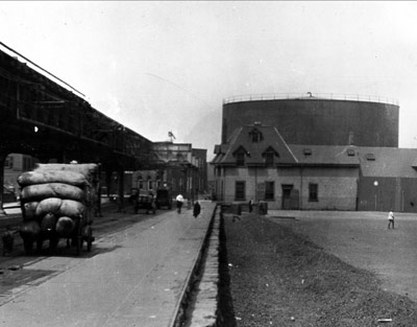

Featured Image: The scene immediately after the accident. The remains of the storage tank can be seen in the upper centre of the image. Image: Boston Public Library

1 Comment