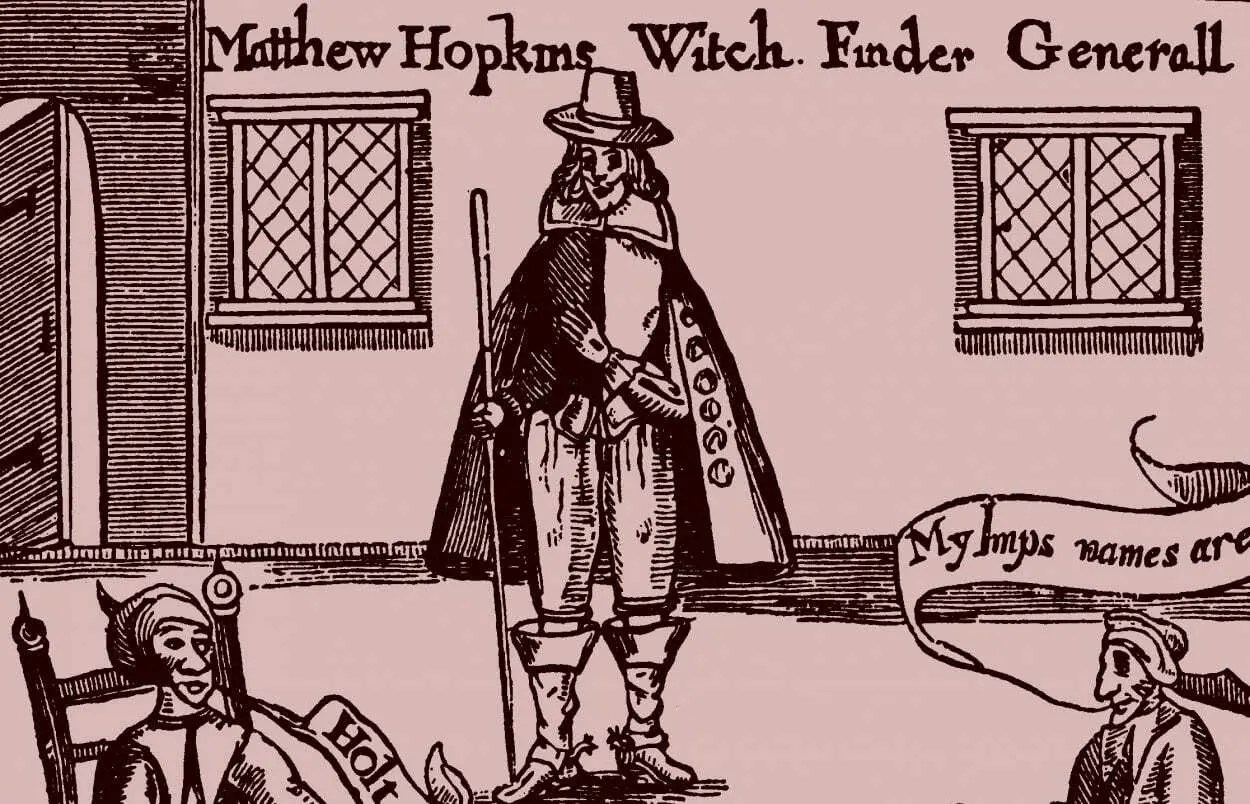

With the self-appointed title of Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins was responsible for the execution of over 100 alleged witches during a career that lasted just three years. Hopkins and his men carried out more executions of accused witches than had happened in the previous 100 years.

There are almost no records of Matthew Hopkins before he began his career at a witchfinder in 1644. Born in Suffolk, Hopkins was the son of a puritan vicar. While historians are unsure of his exact age, they know he was the fourth of his parent’s six children, and must have been born after 1619. In his early 20s, he moved to Manningtree in Essex and purchased the Thorn Inn. He has occasionally been described as training as a lawyer given his skill at delivering evidence during trials, but there is little evidence of this.

Hopkins appears to have settled on a career as a witch-finder in 1644, working primarily with fellow hunter John Stearne across East Anglia as well as areas of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk and Cambridgeshire. The English Civil War had been raging for two years at that point, and the areas patrolled by the pair were largely dominated by staunch puritan supporters of the Parliamentarian faction. Accusations of witchcraft were rife, fueled in part by the high profile Lancaster Witch Trials that had taken place ten years earlier.

Hopkins and Stearne based their investigative methods largely on the Daemonologie, a work covering necromancy and black magic published in 1597 by the then King James VI of Scotland, later also James I of England. Methods of proving that the accused had made a pact with the devil in return for dark magical powers included the so-called swimming test. As it was believed that witches had renounced their baptism, it was thought that water would in turn reject them. Suspects were tied to a chair, or would have one thumb tied to a toe, before being thrown into a body of water. If they floated, they were supposedly proven a witch, and would be dragged out and hanged. If they sank, they were innocent, but would frequently drown anyway.

The swimming test was banned in 1945, meaning Hopkins and his growing number of associates instead focused on searching for the ‘Devil’s Mark’ on a suspect’s body. It was believed that all witches possessed a spot that was dead to all feeling and would not bleed, leading to the use of ‘witch prickers‘ that would poke the accused with knives and needles in search of the devil’s mark. The devil’s mark was said to be the spot where the witch’s familiar, a demonic assistant that took on the form of an animal such as a cat, toad or hare, would feed on the witch’s blood. The discovery of moles or birthmarks on the body were also frequently said to be evidence of the devil’s mark.

In 1647, Hopkins published The Discovery of Witches, outlining his witch-hunting methods and experiences. A few months later, the work was thought to have inspired the accusations and witch-finding methods that resulted in the execution of Alse Young in Connecticut, the first execution for witchcraft in the American colonies. His methods of investigating witches were also employed during the Salem Witch Trials, which resulted in the deaths of 20 accused.

On 12th August 1647, Hopkins died at his home in Essex due to tuberculosis. He was at most 28 years of age, and may have been as young as 25. John Stearne retired as a witchfinder shortly afterwards, returning to his farm and writing his own book, A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft. He had personally been responsible for the conviction and execution of at least 20 accused witches. 19 years later, the Bideford witch trial marked the last executions in England for witchcraft, while the Witchcraft Act of 1735 officially ended prosecutions.