In May 1937, the German-manufactured airship LZ-129 Hindenburg, at the time the largest airship by length and volume, caught fire and was destroyed above Manchester Township, New Jersey. 36 people were killed. Widely known as the Hindenburg disaster, the prominent footage of the blazing airship is widely considered to have brought an end to the viability of passenger travel by airship.

Zeppelins

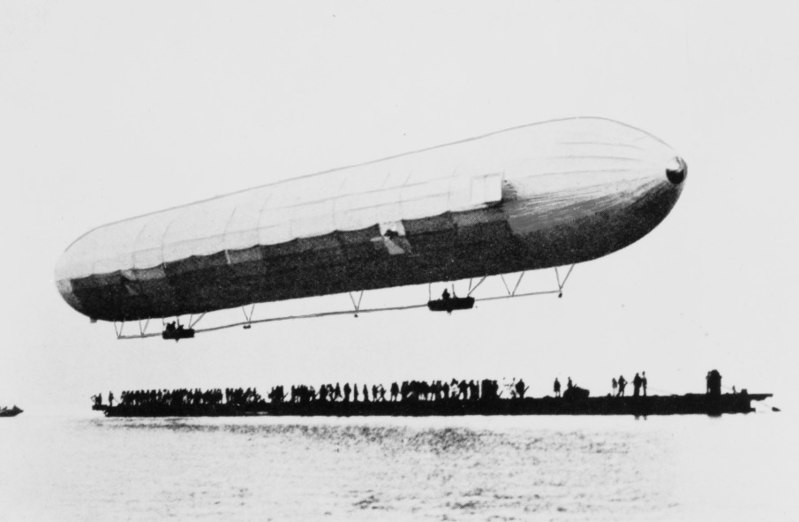

Airships came about through various attempts between the 17th and 19th centuries to find a method of adding propulsion to hot air balloons. This process culminated in the maiden flight of Zeppelin LZ1 in 1900, the first in a series of what became the most successful line of airships: zeppelins. Their success means that for many, airships themselves are referred to as zeppelins. Named for Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, an early developer of airship designs, LZ1 had mixed fortunes on its first flight, carrying five passengers 3.7 miles in less than 20 minutes before an engine failed and it was forced to make an emergency landing. It flew twice more before being dismantled for scrap. Six years later, reformed airship manufacturer Luftschiff Zeppelin launched the LZ2, considered the more direct ancestor of later zeppelin designs.

A sister ship, LZ3, was the first aircraft purchased by the German military. Zeppelins were used by the German Imperial Army during World War I as long-distance bombers, employed against Belgium, France and even the United Kingdom. While their impact was limited, they provoked widespread alarm and are cited as a major reason for the formation of the Royal Air Force in 1918.

In 1926, after restrictions placed on aircraft manufacture in Germany were relaxed, Luftschiff Zeppelin developed the Graf Zeppelin, the first commercial, transatlantic passenger service. Graf Zeppelin travelled over a million miles during its operation, operated by a crew of 36 and carrying 24 passengers. It was the first airship to circumnavigate the globe, as well as the first flight across the Pacific Ocean. Design work for an even bigger airship began in the late 1920s.

This design process resulted in the Hindenburg class of airship, of which two were made: LZ 129 Hindenburg and LZ130 Graf Zeppelin II. The latter, intended to replace its namesake, never entered service.

Built entirely from an aluminium alloy known as duralumin, the Hindenburg was 235m long and 41m in diameter. It carried cabins for 50 passengers, with a crew of 40. As with earlier zeppelins, it used bags of hydrogen gas to provide lift. A funding deal was reached with the Nazi Party after they rose to power in Germany, providing 11 million marks of investment into the development of the Hindenburg in return for using it in propaganda and for the swastika to be displayed on the airship’s tail fins.

The Hindenburg Disaster

After a first flight on March 4th 1936, the Hindenburg made 10 trans-Atlantic trips that year. To mark the start of the 1937 season, it conducted a round trip to Rio de Janeiro before embarking on the first of 10 trips between Europe and the United States scheduled for that year. Already behind schedule for arrival in the US and a fully booked return flight, the Hindenburg was forced to delay its planned landing at Naval Engineering Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, due to thunderstorms. It began its final approach to land at around 7pm local time, half a day behind schedule.

Delays amongst the ground crew forced the zeppelin to make rapid turns and to valve gas to try to brake the aircraft safely, while a further mistake on the ground resulted in the starboard mooring being over-tightened by a ground winch before the port line had been secured. Shortly after, eyewitnesses reported fluttering fabric as if gas was escaping, while other reported a blue glow around the ships. Moments later, flames began to appear.

Eyewitnesses differed on where the fire originated, but all agreed that the highly flammable gas cylinders used to generate lift were quickly engulfed, before the rear of the airship exploded. As the stern of the ship disintegrated the bow was forced upwards. When the tail of the ship struck the ground, it drove flames the length of the remaining hull and out of the nose, killing most of the crew manning the bow. While the hydrogen burned away quickly, diesel fuel continued to burn for hours.

It is estimated that it was less than 40 seconds between flames first being spotted and the Hindenburg crashing to the ground. Chief Petty Officer Frederick Tobin, in command of the US Navy landing party for the airship on the ground, rallied his men with the now famous cry of ‘Navy men, stand fast!’ before leading a rescue operation despite the extreme flames.

35 of the 97 people on board the zeppelin were killed, including 13 passengers and 22 crew. Almost all the survivors were badly burned. One ground crewman was also killed. Commanding officer Captain Max Pruss survived despite severe facial burns that required extensive reconstructive surgery. Captain Ernst Lehmann, who was on the airship as an observer, died in hospital the following day.

Theories

What caused the fire that destroyed the Hindenburg has never been conclusively proven. At the time of the disaster, a popular theory was that the airship had been sabotaged. Hugo Eckener, former head of Luftschiff Zeppelin, favoured this theory, relating that he had been threatened in the weeks leading up to the accident. Charles Rosendahl, commander of Lakehurst air base, agreed, as did Hindenburg captain Max Pruss.

For proponents of sabotage, passenger Joseph Spah tends to be favoured as the potential culprit. A renowned acrobat, Spah had brought along a german shepherd dog as a gift for his children, and had made regular trips to feed it where it was kept in a freight room at the stern of the ship. He was also rumoured to have told anti-Nazi jokes during the trip, while his skills as an acrobat are pointed out when considering his ability to climb up into the airship’s rigging to plant a bomb.

Writer A.A Hoehling theorised that crew member Erich Spehl, who died in hospital following the disaster, had sabotaged the Hindenburg. Spehl’s wife was known to have links with communist and anti-Nazi groups in Germany. A further suggestion is that Hitler himself ordered the sabotage in retribution for Hugo Eckener’s anti-Nazi opinions.

Since Hoehling’s 1962 publication, most historians have dismissed theories of sabotage as lacking any credible evidence. One hypothesis is that the fire was started by an electric spark due to a buildup of static electricity on the airship. Others theorise that it was struck by lightning, or that the fire was caused by an engine failure. Other researchers have focused on what caused the hull of the airship to be consumed by flames so quickly, with proponents split between those in favour of venting hydrogen being responsible and those that argue it was caused by a type of incendiary paint that had been used on the outer hull.